If you've ever pasted a few numbers into ChatGPT and gotten a convincing answer back, it's tempting to think: "Nice, this can replace my calculator, my spreadsheet, and maybe my junior analyst."

My experiments below, together with the last few years of research on large language models (LLMs), say: not so fast.

In this explainer I'll walk through:

- How LLMs actually "compute" something as simple as 2 + 2

- Why they can be near-perfect on some math tasks and terrible on others

- What the following experiments reveal about failures on longer arithmetic and multi-step word problems

- What this means for finance, audit, and tax professionals who are already using GenAI in day-to-day work

- A practical "math safety" checklist you can adopt for your own GenAI policies

1. How LLMs really "calculate" 2 + 2

Modern LLMs like GPT-4 are transformer models trained on huge corpora of text to do one thing: predict the next token (i.e., piece of text) in a sequence. There is no built-in calculator or explicit arithmetic module in the base model. When we ask "What is 2 + 2?", the model is not running an internal version of Excel. Under the hood, a few things happen:

Tokenization

The text "2 + 2" is split into tokens like "2", "+", "2". Each token becomes a vector in a high-dimensional space.

Pattern matching over training data

During training, the base model has seen billions of snippets including "2 + 2 = 4", flashcard-style arithmetic, code examples, textbook problems, etc. The internal parameters have adjusted so that, when it sees the token sequence "2 + 2 =" (or similar), the token "4" has very high probability as the next output.

Soft algorithmic behavior (sometimes...)

For tiny problems like 17 + 58, the model can't just rely on direct memorization of every possible pair. There are too many combinations. Instead, transformers can approximate algorithm-like behavior (such as carrying digits) by layering attention and non-linear transformations. But this behavior is approximate and often degrades sharply as numbers get longer (e.g., 6- or 7-digit arithmetic) or operations get more complex (multi-digit multiplication).

Chain-of-thought (CoT) as a "scratchpad"

When you prompt models to "show your working," they generate step-by-step reasoning before giving a final number. CoT improves performance on many math benchmarks but still doesn't turn the LLM into a reliable symbolic math engine. It's a structured way of doing the same next-token prediction.

Overall, LLMs are probabilistic pattern matchers (or "stochastic parrots", as some researchers have called them), not deterministic, rule-based theorem provers. They emulate arithmetic by learning statistical regularities in text, not by implementing the exact algorithms you'd write in code.

That distinction is the foundation for understanding where they shine. At the same time, this is exactly where they fail in dangerous ways.

2. What my experiments show: From perfect sums to broken multiplication

I ran two sets of experiments using OpenAI's API, focusing on a compact model (GPT-4o-mini) with temperature set to 0 (deterministic outputs).

Experiment 1: Small, fixed dataset (Everything looks perfect!)

First, I tested four very simple categories:

- 1-digit addition (e.g., 2 + 2, 7 + 8)

- 2-digit addition (e.g., 17 + 58)

- 3-digit addition (e.g., 724 + 589)

- Short, single-step word problems (e.g., "Alice has 3 apples, Bob has twice as many...")

Each category had 4 fixed problems. I ran 50 iterations, with all 16 questions asked each time (800 API calls total).

Result: 100% accuracy in every category, every run!

If you only ever tested a model this way, you'd come away believing: "This LLM is rock solid at basic arithmetic and simple word problems. Let's use it for everything." That's exactly the kind of overconfidence many teams fall into.

Experiment 2: Larger, randomized dataset (The cracks appear)

Next, I scaled up and randomized:

- 1-digit addition: random sums like 7 + 2

- 3-digit addition: random sums like 483 + 719

- 6-digit addition: random sums like 394182 + 507913

- 2-digit multiplication: random products like 37 x 84

- 4-digit multiplication: random products like 3847 x 7291

- Multi-step word problems: involving quantities, rates, and small logical chains

For each category, I generated 40 random problems, then ran 10 iterations per category with re-randomization. That's enough to average out quirks and get a sense of variability.

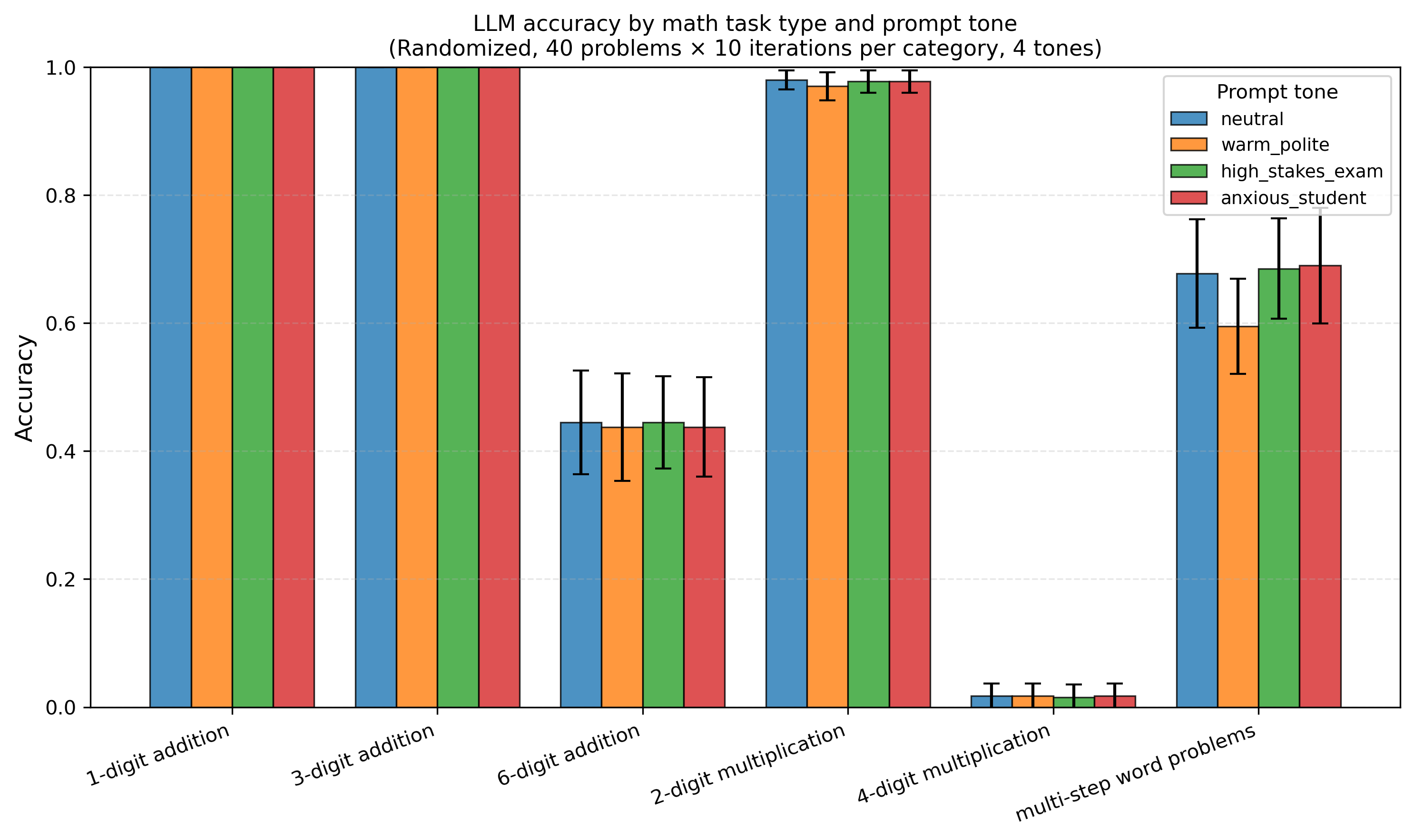

The results (from these ~2,400 API runs):

- 1-digit addition: ~100% accuracy

- 3-digit addition: ~100% accuracy

- 6-digit addition: ~44% accuracy (with noticeable variance across runs)

- 2-digit multiplication: ~98% accuracy

- 4-digit multiplication: ~2% accuracy (basically random, not better than guessing)

- Multi-step word problems: ~67% accuracy, with moderate variance

Accuracy across different arithmetic task categories

Same model. The model is near-perfect for easy addition and very strong for 2-digit multiplication. Performance collapses on 4-digit multiplication. In fact, almost always wrong. Multi-step word problems land in the messy middle: sometimes right, but not reliably so.

You might wonder, "Doesn't ChatGPT solve this using Python now?" Yes, consumer versions like ChatGPT Plus or Copilot can detect math problems and write hidden Python code to solve them perfectly. However, my experiments test the raw LLM API, which is how most enterprise financial tools and automated audit pipelines are currently built. If you integrate a model into your compliance workflow without explicitly configuring a code-execution sandbox, you are relying on the probabilistic "mental math" shown above.

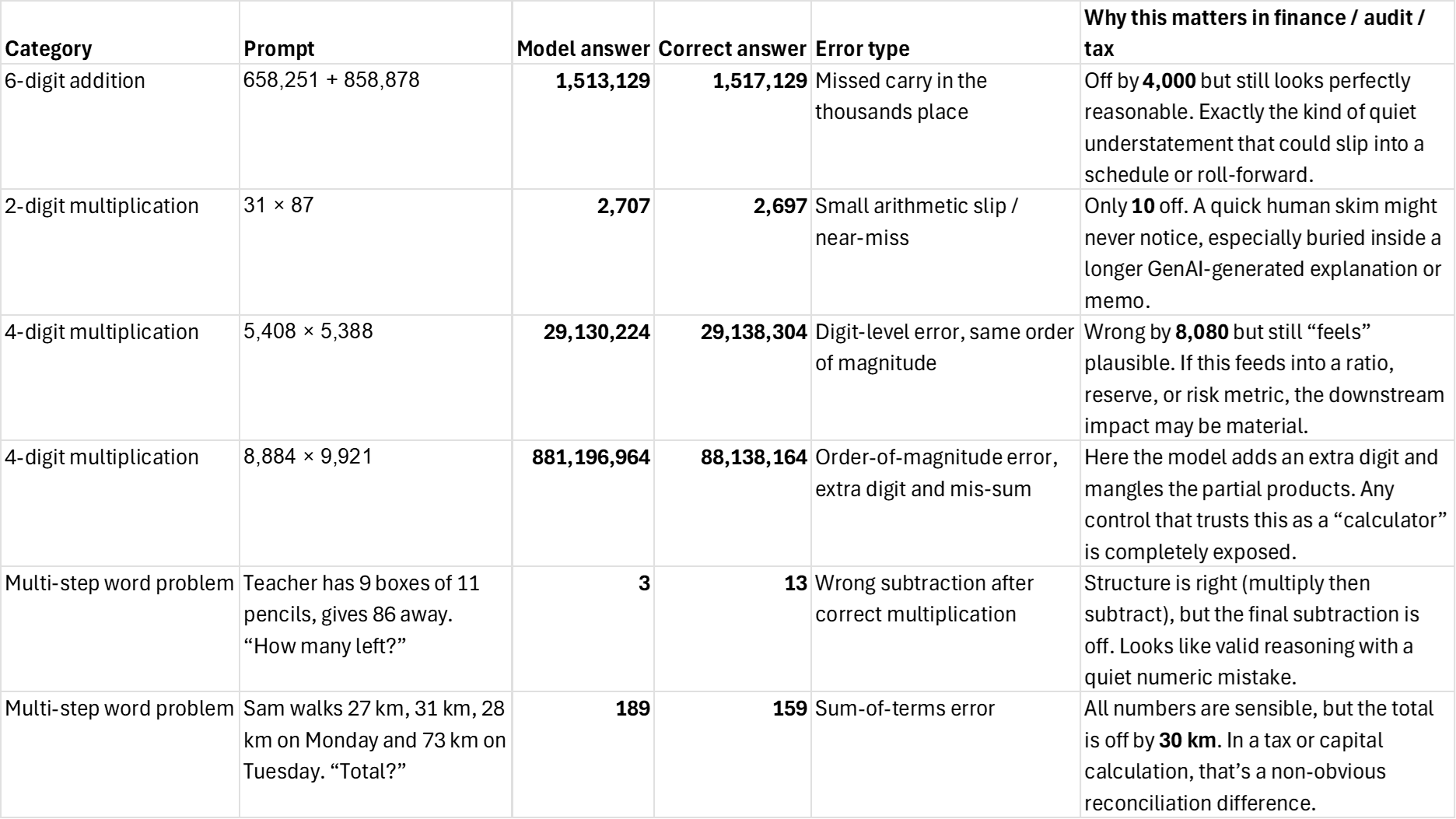

Error gallery: What LLM math mistakes actually look like

The pattern here is worrying for regulated work: the model's mistakes are rarely obvious nonsense. They are plausible numbers that are off by a few tens, hundreds, or an extra digit. In financial reporting, tax, or capital calculations, that's exactly the kind of quiet error that slips into a spreadsheet and becomes a disclosure.

Examples of LLM calculation errors

These patterns line up strikingly well with what we see in current research: LLMs can perform small-scale arithmetic reliably but often fail to generalize to longer numbers without explicit algorithmic modules or special training. Even large models with math-focused training still make non-trivial mistakes on hard competition-level problems.

3. Why this happens: Pattern matching vs. rule-following

To see why 4-digit multiplication fails where 2-digit multiplication mostly works, it helps to distinguish two paradigms:

A calculator (rule-based system)

A calculator or a Python script implements exact algorithms for addition, multiplication, etc. It has guarantees: every 4-digit x 4-digit product will be correct (barring hardware errors). It is deterministic and compositional. We can stack operations indefinitely.

A large language model (statistical sequence model)

An LLM has no built-in concept of "number". 33434325847 is just a token vector. It has learned associations like "x is often followed by a number that 'looks like' the product." It can approximate algorithms via its layers and attention patterns but doesn't enforce them as rules.

Research on arithmetic in LLMs shows that:

- Models often memorize local patterns (e.g., parts of the multiplication table, short sums).

- They sometimes learn quasi-algorithmic shortcuts, but these tend to break as the problem length exceeds what they saw during training or what their architecture can reliably encode.

- Multiplication is particularly fragile because every digit interacts with every other digit in non-linear ways. The math operation simply becomes a harder function for a pattern-matcher to approximate than addition.

In other words: 2-digit multiplication lives near the "seen patterns" regime because lots of examples in the training data and limited combinatorial explosion. 4-digit multiplication lives in the "must truly implement an algorithm" regime, where the model's approximate internal arithmetic is exposed as brittle and fragile.

4. Why this matters for finance, audit, and tax

If you work in finance, audit, or tax, you live in a world where numerical errors are not just embarrassing, because they can become regulatory events.

At the same time, regulators and industry bodies are actively exploring how AI and GenAI fit into financial services and compliance:

- The Financial Stability Board highlights both the efficiency potential and systemic risks of AI, including model risk and operational failures.

- The U.S. Treasury notes GenAI is already being explored for regulatory reporting, risk management, and compliance automation.

- Oversight bodies like the Government Accountability Office emphasize that AI in financial services must be governed through existing risk management and model governance frameworks.

- Industry guidance from firms like IBM stresses integrating GenAI into compliance with robust control frameworks and validation processes.

- Audit regulators like the UK's Financial Reporting Council are already warning that firms aren't adequately tracking the impact of AI tools on audit quality.

The very practical message the above experiments show: Treat LLMs as extremely capable junior analysts who are surprisingly bad at some very specific kinds of arithmetic.

Concrete risks for compliance teams

Here are the kinds of failures the chart implies:

- Hidden calculation errors in complex tax or accounting flows: A long chain of allocations, FX conversions, and rate applications may involve "4-digit multiplication"-style complexity. If an LLM is allowed to compute intermediate numbers directly, it may silently insert wrong values that still "look plausible."

- Inconsistent replicability: With temperature > 0 or prompt variations, the same question can yield different numbers, further undermining auditability and replicability.

- Hallucinated formulas and rates: Even when the arithmetic step is correct, the inputs (tax rate, FX rate, threshold) might be invented or misremembered if not explicitly provided.

- Compliance and model risk: If GenAI is used to produce values that flow into regulatory filings, capital calculations, or tax returns without independent verification, we are in classic "model risk" territory, but with much less transparency than traditional models.

5. A practical "math safety" framework

Rather than banning GenAI outright, it's more useful to draw a clean line between where LLMs are strong and safe enough with good controls, where they are useful but must never be the final source of numbers, and where they simply shouldn't be used for math at all.

Green Zone: Recommended uses

These are use cases where GenAI's strengths align with our risk appetite:

- Explaining calculations, not performing them: "Explain how to compute deferred tax on temporary differences." "Walk me through the logic of IFRS 15 revenue recognition step-by-step."

- Designing formulas, queries, and scripts: "Write an Excel formula to compute weighted average cost of capital given these inputs." "Generate Python / SQL to aggregate transaction data for VAT reporting." We then run the code in a controlled/sandbox environment, where arithmetic is exact.

- Generating test cases and sanity checks: Ask the LLM to produce example ledgers, tax scenarios, or reconciliation cases that you then feed into your own systems to validate logic.

- Drafting documentation and control narratives: Policies, audit workpapers, process descriptions, and commentary around numbers are ideal GenAI territory.

Yellow Zone: Allowed with strong controls

These uses can be valuable but must be paired with deterministic tools:

- Scenario analysis on synthetic data: Use the LLM to set up scenarios, assumptions, and logic; feed those into Excel / Python for the actual computations.

- Automated "copilot" for spreadsheets or data analytical tools: Let the model help you build formulas, pivot tables, and dashboards, but never accept a numeric result without verifying that the underlying formula runs in the host tool.

- First-pass checks on manual work: You can paste in a calculation and ask the LLM to check it. But only as one of several review mechanisms.

Control principle: LLMs can propose or critique the math, but the final numbers must come from a system that's designed to do arithmetic.

Red Zone: Avoid or explicitly prohibit

These are use cases your AI policy should flag as not allowed (or only allowed with a formal model-risk approval):

- Using GenAI chat directly to compute tax payable on real ledger data

- Producing numerical values for regulatory or statutory filings

- Performing large-scale reconciliations or allocations where no independent calculator is involved

- Generating final interest, discounting, or valuation numbers

My earlier results (given the ~2% accuracy on 4-digit multiplication?) are a powerful reminder that: if the model is wrong 98% of the time on a basic numeric operation, we simply cannot treat it as a calculator for high-stakes workflows.

6. The bottom line

For non-technical colleagues, we can condense all this into three simple rules:

- Use GenAI to understand the math, not to be the math.

- If the number goes to a regulator, a client, or the tax authority, it must come from a real calculator, spreadsheet, or code. It cannot come from a chat box.

- Treat every numeric answer from GenAI as a suggestion, not a fact, unless you've independently verified it. Click, read, and confirm.

Large language models are already transforming how finance, audit, and tax professionals read, write, and reason about complex rules. But when it comes to doing arithmetic, they're powerful mimics, not reliable calculators.

- On small, familiar problems (1- to 3-digit addition, simple word problems), they can be near-perfect.

- As the structure becomes more complex (6-digit addition, 4-digit multiplication, multi-step quantitative reasoning), their performance can degrade or even collapse. No better than flipping a coin.

- Regulators are watching closely, and the emerging consensus is clear: GenAI must sit inside a robust control framework, especially when numbers feed into financial reporting and compliance.

Used wisely, LLMs can free skilled people from rote work, help document and test controls, and deepen understanding of complex standards. Used as a black-box calculator, they're a quiet source of model risk.

Let LLMs explain the math. Let code and spreadsheets do the math. That single separation will save you from the worst kind of model risk, where numbers that look plausible and are simply wrong.